These days, it seems like an impossibility. NFL teams in both Green Bay and Milwaukee? But in the league’s nascent years, it actually happened. And the NFL’s Milwaukee Badgers almost killed the league by participating in one of the NFL’s most notorious scandals.

This weekend, NFL fans were treated to the sight of the Tennessee Titans being destroyed by the New England Patriots by a 59-0 score. Yet on December 10, 1925, the Milwaukee Badgers took part in a 59-0 pounding that historians say corrupted the league, and cost Milwaukee their NFL franchise.

In 1925, the NFL was a very different league. Teams such as the Pottsville Maroons, Akron Pros, Frankford Yellow Jackets, Canton Bulldogs, Hammond Pros, and Duluth Kelleys dotted the Midwestern landscape. Early versions of the league also featured teams in Racine and Kenosha. (In 1921, the Twin Cities hosted the Minneapolis Marines, which is fitting given the Vikings\’ future love of boats.) In many cases, games in these middle-sized cities outdrew matches in cities like Detroit and Chicago, where professional football remained a fringe sport. (Football would soon see an explosion in popularity with the Chicago Bears’ signing of Red Grange out of the University of Illinois.)

In addition to the league being geographically smaller, the way the game was played was also very different than the game we know today. Teams had sixteen players, most of whom played both ways. There were no hash marks on the field, so the next play began wherever the last play ended – if the runner went out of bounds, the ball was placed adjacent to the out of bounds line, and the team usually had to waste a play just to move it back into the middle of the field.

In addition to the league being geographically smaller, the way the game was played was also very different than the game we know today. Teams had sixteen players, most of whom played both ways. There were no hash marks on the field, so the next play began wherever the last play ended – if the runner went out of bounds, the ball was placed adjacent to the out of bounds line, and the team usually had to waste a play just to move it back into the middle of the field.

Incomplete passes into the endzone were ruled touchbacks, with the team on defense receiving the ball. Yards were often so hard to come by, teams would often punt on second and third down when backed up in their own territory. In fact, if a punt returner fielded a punt near his own end zone, he would often just turn around and punt the ball back to the other team rather than attempt a return. Coaching from the sideline was forbidden (a strategy employed by the Packers during Ray Rhodes’ season as coach.) The forward pass was seen as a desperation move.

Since many teams operated either at a loss or with a very small profit margin, the league allowed teams to discontinue play in the middle of the season if things weren’t going well. This was the case in 1925 for the ragtag Milwaukee Badgers, who began the season 0-5 and were outscored 132-7, which forced them to fold up shop for the remainder of the season. Playing at Borchert Field, this Badger team featured future Packer NFL Hall of Famer (and River Falls native) Johnny “Blood” McNally. The team was barely newsworthy in Milwaukee, with most of the sports section headlines granted to either Marquette men’s basketball or Red Grange’s 1925 barnstorming tour with the Chicago Bears.

As the season came to a close, the Chicago Cardinals trailed the Pottsville Maroons in the standings by mere percentage points. The Maroons finished the season 10-2, capping the season with a 21-7 win on December 6th against the Cardinals, who dropped to 9-2, with one tie. The game, which was presumed to be the league championship game, barely warranted a mention in the Milwaukee Sentinel.

(And if you want a wildly entertaining look at how sports stories were written in 1925, read the actual story here. The article ends with: “There is a peculiar paradox in the final summing up of the game. The defeated Cardinals scored the most first downs, counting seventeen to the Miners’ eleven. The Chicagoans also completed sixteen forward passes from a total of thirty-five attempts, while the Pottsvillers scored only five out of ten attempts. But that is football!”)

But the Cardinals weren’t about to accept defeat. Instead, their owner, Chris O’Brien, scheduled two more games at the end of the season in order to push their record ahead of the Maroons. One of these games was scheduled against the Milwaukee Badgers, whose players had quit mid-season. Since many of the Badgers’ players weren’t available to play in the game, the team recruited four high school boys, gave them fake names, and sent them out to the field. In fact, it was Art Foltz, a Cardinal player, who recruited the high schoolers from his old school, Englewood High.

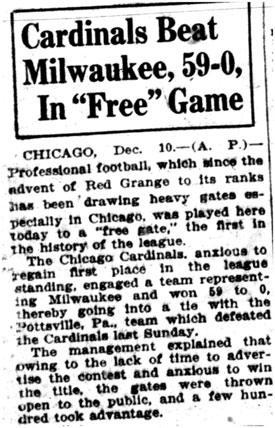

Naturally, the Cardinals pounded the Badgers, winning 59-0. The local newspaper made no mention of the game before it was played, and no admission fee was charged to fans. According to the report, “a few hundred” fans took advantage. The write-up in the Milwaukee Sentinel barely measured two column inches:

The Cardinals also went on to beat the Hammond Pros 13-0 two days later, at which point they declared themselves league champions after going 11-2-1. During the time the Cardinals were lining up those two games to pad their record, Pottsville played a game against a team of Notre Dame all stars, which the league strictly forbade.

Soon, League Commissioner Joe Carr learned of the use of high school players for the Badger-Cardinal game and sternly punished the team and its owner. The team was fined $500 (the entry fee for teams was only $50 at the time), and the owner, Ambrose McGurk, was ordered to sell the team within 90 days. McGurk was also banned from any further association with the NFL for the rest of his life. (The Cardinals’ Foltz was also banned for life, and O’Brien was fined $1,000, despite claiming he didn’t know about the high schoolers. The boys were barred from participation in Big Ten College football.)

Yet despite all the penalties handed down by the league, the Cardinals were declared league champions, and all the records from that year have stood. The Badgers attempted to field a team in 1926, but the $500 fine for the Cardinal game nearly wiped them out. They did win two games in 1926, but quickly disbanded – many of their players went to play for the Pittsburgh Pirates football team, leading many to mistakenly think the Badgers eventually became the Pittsburgh Steelers.

In the meantime, their cousins to the north, the Green Bay Packers, flourished in a much smaller town. (In the 1925 season, the Badgers, coached by Johnny Bryan, went 0-2 against the Packers, losing by scores of 31-0 and 6-0.) The only touchdown the team scored all season was on a fumble recovery by left end Clem Neacy, against the Rock Island Independents.

In the meantime, their cousins to the north, the Green Bay Packers, flourished in a much smaller town. (In the 1925 season, the Badgers, coached by Johnny Bryan, went 0-2 against the Packers, losing by scores of 31-0 and 6-0.) The only touchdown the team scored all season was on a fumble recovery by left end Clem Neacy, against the Rock Island Independents.

Perhaps one of the Badgers’ most notable accomplishments was employing one of the first two African-American players in NFL history. In 1922, after one season with the Akron Pros, Fritz Pollard came to Milwaukee, scoring three touchdowns and kicking two extra points on his way to leading the team with 20 points. Pollard was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2005.

***

In fact, the Green Bay Packers themselves didn’t have the smoothest of entries into the NFL, either. In 1921, Commissioner Carr found out that the Packers had actually been recruiting college students, giving them fake names, and allowing them to play in games. (Incidentally, it is believed that this was Brett Favre’s first season in the league.)

Carr ordered the Packers to disband as a franchise as punishment. But Coach Curly Lambeau desperately wanted back in, pointing out that he had the $50 necessary to purchase a new franchise. But he couldn’t make it to Canton, Ohio for the league owners’ meeting.

Lambeau mentioned his problem to Don Murphy, the son of a Green Bay lumberman, who offered to make the trip down to Canton on behalf of Lambeau in exchange for one thing: he wanted to be on the team the next year. Despite Murphy clearly not being a football player, Lambeau acquiesced, and Murphy went to Ohio and bought the team back.

In 1922, in the first game of the year, Murphy played tackle for the Green Bay Packers for one minute. He then walked off the field and “retired” from football forever.

***

It bears repeating that the NFL was a wild, loosely organized gang of misfits in its first years. Probably the most entertaining team in the league at the time was the Oorang Indians, who called LaRue, Ohio their home (pop. 900.)

Many of the NFL teams at the time were formed strictly as advertisements for certain companies – The Acme Packers, the Decatur Staleys (after the A.E. Staley Company, later the Chicago Bears), etc. But the Oorang Indians were formed to advertise the Oorang Airedale puppy breeding business in the village.

The owner, Walter Lingo, was also a fan of Native Americans – so he staffed the team completely with Indians, who would have the job of advertising his Airedale puppies. As such, he utilized the team extensively during pre-game and halftime shows, which served to promote his breeding business. At several points, Lingo would pluck one of his players from the bench and have him wrestle a bear at mid-field. Other times, there would be Indian shooting exhibitions, with Airedales fetching the marks. The high point, according to historians, was the time Indians were used in a World War I re-enactment against the Germans, with Airedales providing first aid to the fallen soldiers.

Not surprisingly, the team was terrible, finishing 3-6 in 1922.

For more wildly entertaining stories about the early days of the NFL, pick up “Pigskin: The Early Years of Pro Football by Robert W. Peterson.

***

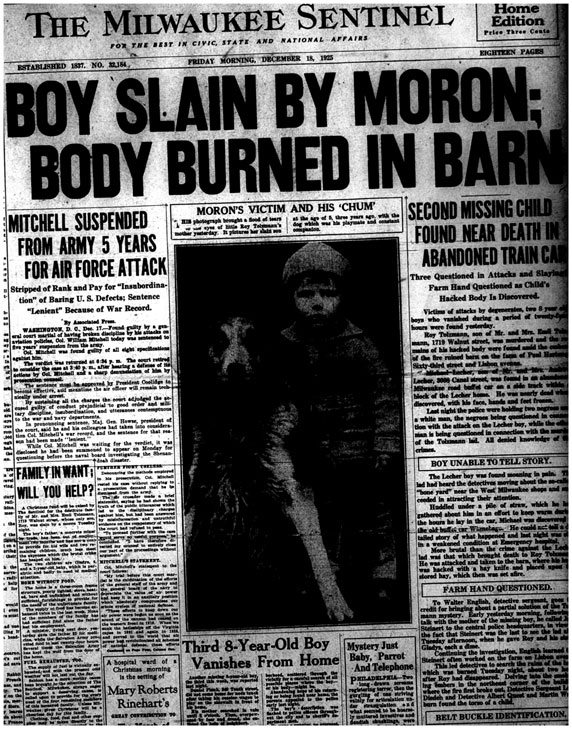

One of the benefits of poring over newspapers from 1925 is finding gems like this. Here’s an actual headline from the Milwaukee Sentinel on December 18, 1925:

Today’s melancholy song: Nick Drake (who killed himself before he gained any notoriety for beautiful songs like this one.)

Leave a Reply