See that pen on your desk? Right over there, by the stapler. As it turns out, that pen is one of the most powerful instruments you can own. The U.S Constitution was written with a pen. Lincoln freed the slaves with a pen. Most importantly, some girl in middle school probably broke your heart when she used a pen to check the “NO” box in response to your sweaty “Do you like me?” query.

In fact, while Wisconsin state government-related interest groups spend millions of dollars on lobbyists to influence lawmakers, that pen on your desk is the most influential implement in state government. It is the entire reason we structure our Wisconsin state and local governments in the manner we do.

Wisconsin residents pay all kinds of taxes. They pay income taxes (which are usually automatically deducted from their paycheck) or sales taxes (which are automatically added to their purchase), or corporate taxes (which are passed through in the form of higher prices.) Yet with all the billions of dollars in taxes Wisconsin citizens pay, one particular levy stands alone in its repugnance. It is the property tax.

Poll after poll demonstrates that Wisconsin residents object to paying the property tax more than any other tax – even if, say, their income tax liability is greater than the amount they pay in property taxes. But it’s all money, after all, so why is paying property taxes so much more painful?

The answer has to do with the physical way in which each tax is paid. When we pay property taxes, that pen must come off the desk and sign a check over to the government. Rather than automatically handing money over to the government, paying property taxes is a proactive endeavor, usually involving the clenching of teeth, irritability, and alcohol consumption.

The painful act of writing a check to the government has far-reaching consequences. For decades, Wisconsin politicians have been myopic in their quest to relieve the property tax burden on individuals. In 1995, Governor Tommy Thompson sent an extra $1 billion to local school districts to buy down the property tax levies around the state. Governor Jim Doyle’s special commission on school funding suggested raising the sales tax in order to replace a portion of the unpopular property tax. Legislative Republicans fought a bloody internecine war in an attempt to pass the Taxpayers Bill of Rights in an attempt to hold down property taxes. Their Democrat colleagues have spent years pushing a plan to exempt a portion of residential property from having to pay taxes. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Clearly, state government is dedicated to keeping you from having to pick that pen up off your desk. But this raises a provocative – and in Wisconsin, almost unspeakable – question:

What if property taxes are the best way to tax?

I recognize that even asking such a question will go over about as well as a complete sentence at the Country Music Awards. But what if there is a case to be made for more reliance on the property tax, and less on income, sales, and corporate taxes?

Obviously, lower taxes and lower spending would be the ideal goal. But if we have to choose one tax over the other, which one does the most good for the economy?

In 2006, conservative Mount Rushmore occupant Milton Friedman re-stated his long-term opposition to taxes, but said “The property tax is one of the least bad taxes, because it’s levied on something that cannot be produced — that part that is levied on the land.”

In other words, taxes on income, sales, and corporations depress activities that are beneficial to a robust economy. They punish work, job creation, and production – all things necessary for the creation of wealth in society. Naturally, the more you tax these activities, the less of them you get – which causes big trouble when the economy starts to recede.

In this month’s Atlantic Monthly, New America Foundation fellow Reihan Salam picks up on this idea, and proposes ending all taxes except for the property tax:

“Chronic revenue shortfalls have crippled local governments ever since, leading to heavier reliance on punishing state income and sales taxes. What if the problem isn’t the property tax at all but rather, well, all other taxes? In 1879, Henry George, a brilliant if slightly crankish autodidact, published Progress and Poverty, a scathing polemic that blamed all economic ills on the private ownership of land. A staunch believer in laissez-faire economics, George found it perverse that we tax productive activities like work and innovative investment while letting landowners grow rich simply because they scooped up property at the right time. In that spirit, George called for a “Single Tax” on the unimproved value of land. There’s a certain compelling logic to the Single Tax that stands the test of time. When you tax income, aren’t you punishing people for working hard? But when you tax an asset like land, you’re simply encouraging the most valuable use of that land.”

In Wisconsin, local governments have levied property taxes since before the state even became a territory in 1836. (It was probably around that time that profanity was invented.) In 1842, Governor James Doty called property taxes “unequal, illegal and highly oppressive.” Wisconsin wouldn’t become a state for another six years.

Since then, one of the primary focuses of the state government has been trying to keep property taxes down. In 1911, when the state began levying an income tax, state government immediately began sending funds to local governments to offset reliance on the property tax.

In the most recent state budget, 55.3% of the state’s general fund appropriations go to local governments for the purpose of holding down property taxes. But this creates an enormous accountability gap, which would be eliminated if the state got out of the business of funding local governments.

Imagine the plight of the typical property taxpayer. If they want to complain about their taxes being too high, they go to the local governments, who blame the state government for not giving them enough money. When they complain to their state legislators, they point out that local governments set property tax rates. Both levels of government blame each other, spending continues to go up, and taxpayers receive no answers.

Shifting taxation to the local level also would benefit civic participation. Studies have show that as more government decisions are moved up to the state and federal levels, the more citizens tend to disengage from civic involvement. When the state takes over more and more of the decision making for schools, fewer and fewer local residents bother to go to school board meetings. When the state micromanages local city, village, and town budgets, fewer people engage in municipal politics at the grassroots level, where decisions are made that most closely affect those constituents.

If state sales and income taxes were cut, and programs like shared revenue reduced (which sends nearly $1 billion per year to local governments) there would be more accountability in how tax dollars are spent. Yes, property taxes would go up to make up for the lost state aid – but then, citizens would be able to more directly affect their tax level and how those funds are spent at the local level.

Furthermore, property taxes are assessed on those that have wealth. They are not necessarily progressive, as everyone in a taxing jurisdiction pays the same rate – but they certainly aren’t as regressive as sales taxes, which force low income people to pay a larger percent of their income to buy things. People that own property tend to have money – and those people may actually do well under a scenario where income taxes are cut and the property tax increases.

Property tax opponents (read: everyone) would argue that property values don’t relate to income – that some senior citizens may be low income, but have a very high value home that they, say, bought for cheap on a lake 50 years ago. Thus, increasing property taxes would hurt those people, as they have little income and high property values.

These individual examples may exist, but in the aggregate, income and property wealth are tied fairly closely.

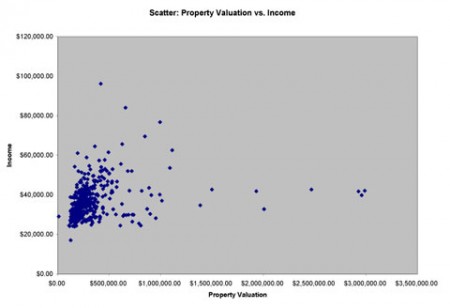

The following chart compares property values to income in Wisconsin’s 426 school districts. As can be seen, there is a tight correlation between how much people make in income (as reported to the State Department of Revenue) and their property values (as reported to the Department of Public Instruction.) There appear to be about eight outliers – school districts with high property values and low incomes – but several of these are special districts. For the other 418 districts, the more they make, the more in property value they have.

Clearly, relying more heavily on the property tax and less on the sales and income tax would be taxing people with more means. Furthermore, reducing sales, income, and corporate taxes at the state level would be rewarding activities that would get the economy moving once again – more incentive for job creation, for advancing in one’s career, and for purchasing goods to aid in business development.

A plan to shift taxes away from economy-boosting activities and on to property taxes has some perils, however.

First, such a plan would need the state’s finances to be somewhat in balance to work. As it is, the state’s structural deficit stands at $2.2 billion going into the next budget. In other words, the state could shift $2.2 billion in spending onto the property tax in the next two years, without having cut a single cent from the sales, income, or property tax. Consequently, there wouldn’t be any stimulation to the private sector – merely an enormous property tax increase without any economic benefit.

Furthermore, shifting taxation from state to local taxes would make it more expensive to own a home. But the plan would have to come with commensurate reductions in other taxes, which could more than make up for that extra expense. If lowering business and income taxes has the stimulative effects that can be expected, more people will have better jobs, make more money, and pay less in income taxes – to the point that it may supersede the increased cost of a home. And for those with low incomes, programs such as the Homestead Tax Credit can be reconfigured to give the largest relief to those who need it the most.

Maybe shifting taxation away from the productive activities that drive our economy would get the state roaring once again. Maybe it would force us all to live in caves. But it is certainly a discussion that will never occur at the Capitol, where “we’ve always done it this way,” seems to be the most influential argument made by lawmakers. And certainly, in a climate where upwards of 80% of citizens are in favor of freezing property taxes, a shift to local control seems about as likely as state legislators turning the Capitol into a bed and breakfast. (Even if a plan included a commensurate sales and income tax cut.)

But we shouldn’t let an arbitrary thing like how we physically pay our taxes get in the way of how we should more equally distribute taxation for the purposes of bettering our state. In fact, perhaps the state could set up a program to pay property taxes automatically out of paychecks, which people don’t seem to mind – as long as it’s out of their sight.

Just don’t stab me with your pen.

-July 30, 2009

Leave a Reply