PART I: ALL OF IT

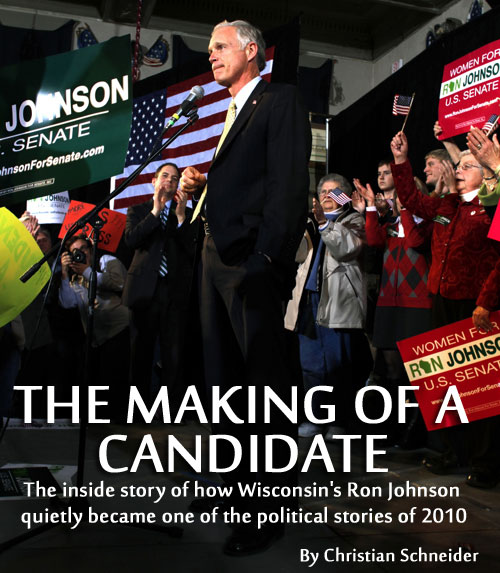

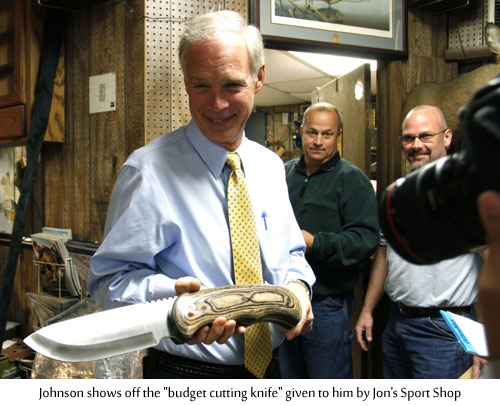

Just by walking down Oregon Street in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, it’s hard to tell that the Fate of Democracy in America resides here. At the end of the street, The Ron Johnson for U.S. Senate campaign headquarters inhabits a large brick building fronted by stately white columns. The building rests across the street from the vast Jeld Wen premium wood door plant, and just north of the Bottoms Up Bar, where t-shirted patrons spend afternoons drinking to forget the problems U.S. Senate candidates promise to solve. (It is one of five bars within one square city block.)

Oshkosh isn’t exactly the epicenter of Wisconsin politics. No statewide political figure has been elected from Oshkosh since 1899, when Emmett Hicks served as the state’s Attorney General. Oshkosh did make statewide political news a decade ago, when one of its adult bookstores found a former state senator offering an undercover police officer the opportunity to “munch” on his privates, thus creating the most entertaining arrest report in Wisconsin political history.

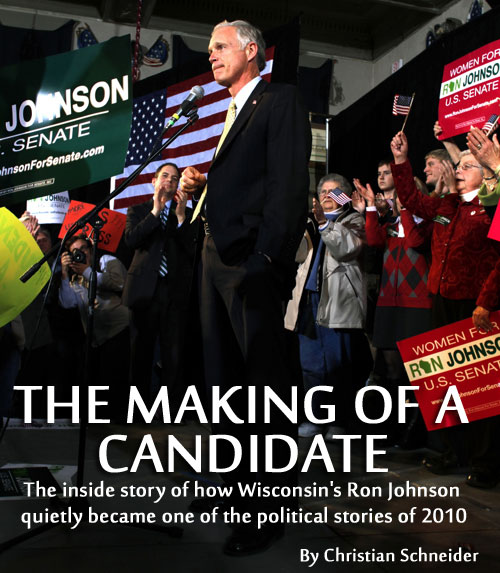

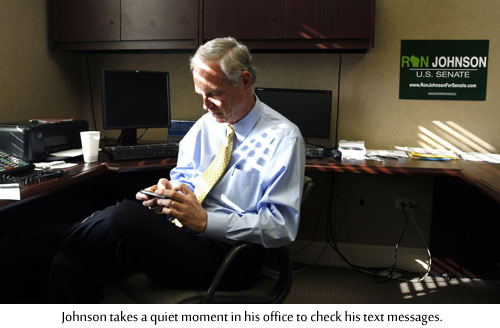

Inside the Johnson headquarters, bespectacled 31 year-old campaign manager Juston Johnson (no relation to Ron) rubs the top of his prematurely bald head. He’s just gotten a call from the Wall Street Journal asking to talk about Johnson’s upstart campaign. “I’m terrible at talking to the press,” he complains, and passes the call off to Kristin Ruesch, his newly minted communications director.

It’s been a dizzying six-week stretch for Juston, as 55 year-old Ron Johnson has gone from being an unknown plastics manufacturer from Oshkosh to getting calls from the Wall Street Journal about his campaign against 18-year Democratic incumbent U.S. Senator Russ Feingold.

Hopes for large Republican electoral gains are high in June of 2010. Low approval ratings for President Obama and the Democrat-controlled Congress have opened up the possibility for Republicans to take back the U.S. House of Representatives – a scenario which had been unthinkable mere months ago. A dyspeptic American public, weary from two years of high unemployment, appears poised to toss out the Democrats they have deemed ineffective.

There are even rumblings that the GOP wave could win Republicans back control of the U.S. Senate, which Democrats hold by a 59-41 margin. The recent election of Republican Scott Brown from Massachusetts has a number of GOP challengers feeling that they can ride a wave of voter discontent with Democrats into the Senate. But in order to regain the majority, Republicans would have to sweep ten heavily contested contests around the country – including races in traditional Democratic strongholds like California, Illinois, and Washington.

Ron Johnson from Oshkosh, Wisconsin, would be the tenth.

Wisconsin has elected one Republican to the U.S. Senate since 1963 (Bob Kasten, who defeated Wisconsin political icon Gaylord Nelson in 1980.) But amazingly, a Ron Johnson win doesn’t seem impossible early in 2010. A new poll from a Democrat pollster has Johnson within two percentage points of Feingold, 45% to 43%, despite Johnson only being in the race for a little over a month.

Feingold is no easy target. Elected since 1992, he has cultivated his reputation as a “maverick,” willing to break ranks with his party on fiscal issues. He aims to be the pluripotent senator – able to adapt to whatever political environment suits him at the time. However, his recent votes for the controversial health care overhaul and the expensive and ineffective “stimulus” bill may have weakened him irreparably.

Feingold’s weakened state has manifested itself in the early polling. Yet Juston is skeptical of the numbers. He notes that even lesser-known Republican Dave Westlake polls at 38% against Feingold, meaning Johnson is only a few percentage points above what’s known in politics as the “ham sandwich” number. (This is the number that a ham sandwich would get if it were placed on a ballot against an incumbent.)

Furthermore, the poll purports to have a sample made up of half 2008 Obama presidential voters and half McCain voters. This makes it seems as if the poll is balanced, but in reality, Obama won Wisconsin by thirteen percentage points – leading Juston to think Republicans may be overrepresented. Then again, it’s only June 30th – it’s entirely possible that we could fighting the machines by the time the general election rolls around in November.

The inside of the RonJon campaign office is vast. (“RonJon” is a nickname some of his staff have come up with for Johnson – they considered “RoJo,” but thought it made him sound too much like a guy who designs sweaters for poodles.) This floor of the building used to be either a law office, or real estate office – nobody can really say, as it has sat dormant for years. The office has been sectioned off into a sea of cubicles, almost all of which sit empty, waiting for the – fingers crossed – eventual army of volunteers. Currently, Johnson has 17 paid staff members.

Strewn around the makeshift office walls are boxes of t-shirts, yard signs, and bumper stickers. It has the look of a campaign office that has unpacked all of its belongings hastily. Mostly because that’s exactly what has happened.

Despite being considered the U.S. Senate race that could regain Republicans the majority in 2010, the campaign can’t seem to get their internet to work. This morning, RonJon is conducting an interview with conservative Milwaukee talk radio host Charlie Sykes. More than three people appear to be streaming the broadcast live over the internet, so the entire network goes down. Throughout the day, depending on how many people are online at the same time, the wireless signal comes and goes. If someone dared to attempt downloading a Lady Gaga album, it could knock the Ron Johnson campaign offline for three days.

Back in his cubicle, amongst the boxes, Jack Jablonski is settling in not looking forward to the long weeks ahead. Jablonski, the 36-year old deputy campaign manager, has run campaigns for Wisconsin state senate candidates for a decade. He recently left a congressional race in Western Wisconsin to help RonJon. He is one of the oldest staffers in the office.

“Oshkosh is like a working man’s Eau Claire,” he says, as one who had spent many nights sleeping under a desk in Eau Claire running other campaigns. He’s miserable and wants to go home. Jablonski’s wife, Courtney, gave birth to his first child, a boy, just weeks ago – and Jack wants to see him.

In his remote cubicle, Jablonski is holding court with the other staffers, detailing a study he read that could bode well for RonJon. Apparently, some political scientists have determined that voters are more likely to support the candidate with the narrower face. It makes them look more trustworthy, or something. These researchers actually used Feingold’s 2004 race against construction company owner Tim Michels to prove their point – Feingold’s face was narrower that Michels’ giant meaty head, so study respondents correctly picked Feingold as the winner by overwhelming margins.

“Ron’s face is even narrower than Feingold’s” Jablonski points out. “Let’s all just go home – it’s a done deal,” he jokes.

It has fallen to the tightly-wound Jablonski to prepare RonJon for the rigors of campaign question-and-answer sessions. (Friends say that Jablonski may be the only person on earth that actually has to drink Red Bull to calm himself down.) The early days of Johnson’s campaign have been beset by verbal stumbles and misstatements, such as when Johnson suggested he was running for office because he heard Fox News consultant (and notable prostitute enthusiast) Dick Morris say that “some rich guy” should take Feingold on. “I told Ron to never utter the words ‘Dick Morris’ in public again,” said Juston.

Clearly, in mid-June, Johnson isn’t exactly a skilled interlocutor, which has become the central focus of his campaign. “Ron is prone to mistakes,” said one staffer, explaining why they were keeping him away from the media for the time being.

One of the times RonJon’s inexperience as a public speaker became most evident occurred in early June, when the new candidate was speaking in front of a conservative group that should have been predisposed to his way of thinking. Johnson was asked a question about illegal immigration, and began giving a good answer.

Johnson was telling the group all about how we need to secure the border and enforce the laws on the books. He could have ended there and been just fine. Then, when he should have stopped talking, he started asking himself rhetorical questions. Johnson, not knowing what was going to come out of his mouth next, said, out loud, “of course, that brings up the question – what do we do with the illegal immigrants that are already here?”

Johnson’s staff was horrified. Clearly, the only reason to ask yourself a hypothetical question out loud is because you probably don’t know the answer. And not knowing things isn’t exactly a strong resume point when applying to be a U.S. senator.

As a result, Jablonski, Juston, and Ruesch began a “candidate boot camp” for the new candidate. They locked Johnson into a room for three days in mid-June, firing questions at him. These quickly became known as the “murder sessions.” Among the questions Johnson was posed:

- Should British Petroleum (BP) be required to suspend its dividend payouts to ensure set aside for liabilities or put it into an escrow fund?

- What do you feel caused the financial crash?

- When is it appropriate to use the filibuster?

- Who is responsible for preserving and protecting the Gulf of Mexico?

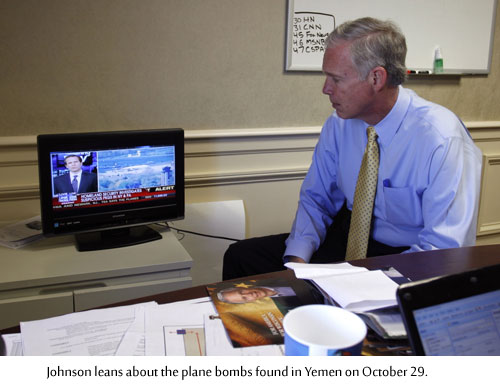

- Is Obama a Marxist?

- Are you the tea party candidate?

- Are you in favor of a Fair or Flat Tax?

- Should we audit the Fed?

Both Jablonski and Juston acknowledge that RonJon is a smart guy. “He’s said ‘every day I wake up, my goal is not to say something that will completely sink my campaign,’” recounts Juston. “And he’s a very willing learner – he’d sit and study policy papers all day if he could,” he said. “But he’s also very impatient and sensitive to his own vulnerabilities. He can’t stand just saying ‘I don’t know,’ when asked a tough question. It’s our job to teach him that sometimes it’s okay to give a 10 to 15 second answer, then pivot to jobs and the economy.”

Despite Johnson’s willingness to learn, these behind-the-scenes question and answer sessions often got testy. At times, Johnson’s obduracy ground the meetings to a halt. He didn’t think he’d be asked many of the questions his staff posed him. They often had to go back over issues several times.

For instance, staff told him three separate times not to say he’s a better candidate than Dave Westlake because he has more money. Then, at a candidate forum in Brookfield, Johnson answered a question about why he’d be a better candidate by essentially saying he had more money.

Through the murder sessions, Jablonski says he became convinced Johnson was smart and well-read enough to pull this off. But Johnson was clearly a neophyte, while Feingold has been at the political game for over 30 years now. “For eighteen years, taxpayers have been paying Russ Feingold to know everything there is to know about the federal government,” Jablonski says. “And Ron has to learn it all in, like, two weeks. Can you name anyone in the state who would be able to step into a situation like that?”

In June, Democrats are betting Johnson can’t. That is why they’ve put a tracker on him – a paid staffer carrying a video camera, recording Johnson’s every utterance. Johnson’s staffers say the tracker follows within two feet of Johnson any time he’s in public, which tends to creep out many of the voters RonJon talks to. All so they can capture a “Macaca moment.” (In 2006, Virginia Senator George Allen’s campaign was felled by a tracker who caught him on camera calling an Indian-American questioner “Macaca.”)

Johnson’s staff said the Democratic tracker was particularly obnoxious during 4th of July parades in Oshkosh, Franklin, Hartford, Menomonee Falls and Sheboygan, where Johnson tried to walk the parade route and talk to people with his tracker by his side. Staffers said they thought about giving the tracker some campaign lit and asking him to hand it out, as long as he was going to be following Johnson everywhere. They openly wondered if they should hire a tracker to follow the tracker, just to show how obnoxious the whole situation was. (They mention Republican gubernatorial candidate Scott Walker also has a Democratic tracker, but that his tracker is actually a pretty cool guy.)

Over in her own office, Kristin Ruesch has just finished the call with the Wall Street Journal that Juston sent her way earlier in the day. She’s still waiting for Oshkosh’s charms to present themselves to her, as she’s only been a part of the campaign for a little over a week – having left her position as communications director of the Republican Party of Wisconsin. In order to stay motivated, she ends each day by reading a short passage from former President Bush advisor Karen Hughes’ book, “Ten Minutes From Normal.” (Ruesch is on the board of Wisconsin Women in Government, and got to meet Hughes, her hero, just three months ago.)

The call from the Wall Street Journal was to find out whether Johnson has fallen out of favor with the Tea Party movement, which many people believe helped spawn his campaign. In the early days of his candidacy, RonJon has come out in favor of the Patriot Act, which many libertarians in the right-wing Tea Party movement believe to be an infringement on their civil liberties. Johnson believes it is necessary for the protection of our country, but several Tea Party groups have opposed his candidacy as a result. (One such group, the “Wisconsin 9/12 Project,” released a “poll” of its members that showed Dave Westlake beating Johnson 95% to 5% – which likely means exactly 20 people took the poll.)

This is quite a sea change for Johnson, whose first major public appearance as a potential U.S. Senate candidate took place at a Tea Party rally on the Wisconsin Capitol lawn on April 15th. On Tax Day, Johnson gave an impassioned speech before conservatives and libertarians – at the time, he was just known as “the rich guy who might run against Feingold.” And it took him a full month after that speech to formally declare his candidacy.

In May, Feingold was more than willing to play up Johnson’s connections to the Tea Party. In Kentucky, “Tea Party candidate” Rand Paul won a landslide victory in the Republican U.S. Senate primary, and celebrated his victory by announcing that he’d like to see a portion of the 1964 Civil Rights Act repealed.

After the Rand Paul Civil Right imbroglio, Feingold pounced on RonJon. “[Johnson] refused to say whether he favors the continuation of Social Security and Medicare. He hasn’t even said he supports the Civil Right Act,” Feingold said in a June 16th interviewwith Politico.com.

Feingold also took some shots at Johnson during the senator’s speech to the Wisconsin Democratic Convention on Friday, June 11th. Feingold said he fought against deregulating the banks in 1999, while “Mr. Johnson was silent.” Feingold said he fought against President Bush’s policy to let corporate America “run wild,” and, again, “Mr. Johnson was silent.”

The mere mention of these Feingold quote gets Jablonski red-faced with anger.

“So let me get this straight – Ron Johnson is just some guy up in Oshkosh running a business and employing people, and Feingold thinks he should be putting out press releases saying he supports the Civil Rights Act? What the fuck? Maybe we should issue a statement accusing Russ Feingold of never saying he opposed child abuse. Or say ‘Russ Feingold sat idly by while Brett Favre bought a cell phone.’ It’s ridiculous.”

Furthermore, later in the Politico interview, Feingold actually portrayed himself as the Tea Party candidate, pointing out that he agrees with many of their factions on the Patriot Act. Feingold said Johnson “doesn’t match up with some of their views. He’s trying to use the label of the tea party, but under closer scrutiny, they’re going to realize they don’t match up.”

This puzzled Ruesch. “So in the same interview, Feingold claims Ron is a racist because he’s a Tea Party member, but then criticizes him for not being enough of a Tea Party member? Which is it?” she asks.

One of Feingold’s initial shots at Johnson dealt with RonJon’s wealth. Feingold pointed out that Johnson would be the 70th millionaire in the Senate, and pleaded for a little “economic diversity.”

When Johnson first entered the race, he said he would spend $15 million on the campaign if he had to. From this figure, political experts tried to extrapolate how much Johnson was actually worth – $100 million? $200 million?

In fact, Johnson was worth almost exactly what he said he would spend – around $15 million. When asked by Washington Post columnist George F. Will how much of his personal wealth he would use on the campaign, he said “all of it.”

But Johnson was used to giving away his money. Between 2005 and 2009, Ron had donated $2.2 million to charity, much of it to Catholic schools in the Oshkosh area. But the fact that RonJon often gave gift anonymously hurt him when trying to accumulate name ID for his campaign. “He’s a rich guy in a small town, but nobody knows who he is,” said Juston.

A millionaire challenger is actually something Feingold clearly dreaded. Part of the famous McCain-Feingold campaign law was a provision that prevented independently wealthy candidates from spending their own money on their campaign. This so-called “millionaire’s amendment” was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2008.

Feingold likely knew that the only way a challenger could catch up with his $5 million warchest was for a millionaire to spend his or her own money. So he authored a law to keep them from taking him on. But now, thanks to the law being declared unconstitutional, Feingold had a capable millionaire on his doorstep.

While the campaign dealt with these little brush fires, Juston knew these Feingold jabs were tepid compared to what was headed their way as the campaign progresses. In fact, he was surprised Feingold and his surrogates hadn’t been more aggressive up to that point. He said that if he were running the Democrats’ campaign at that point, he’d be spending millions to “kill the Johnson campaign in its crib.” He notes that currently, Johnson “doesn’t have the resources or staff infrastructure to respond to anything big they could throw at us.”

Soon, he would get his wish.

PART II: RONJON GOES ROGUE

Russ Feingold began his advertising campaign in earnest on July 6th, when he commenced running a 60-second radio ad called “Penny Pincher.” The ad, which features only Feingold’s own voice, bragged about the senator’s vote against the 2008 bank bailout, saying that in Wisconsin, “we pinch our pennies.”

The ad is emblematic of the way Feingold sees himself – despite being one of the Senate’s most stalwart liberals, he seems to have convinced himself that he is a thrifty protector of taxpayer dollars. Ads like these essentially serve as political mascara – when he doesn’t like the face he has, Feingold just draws one on that he likes.

In the same ad, Feingold attempts to bolster his credibility as a fiscal conservative by touting his plan to end pay raises for members of Congress – a transparent strategy to run against the body in which he had served for 18 years.

The calculus is easy to follow: in the preceding legislative session, Feingold voted for a number of bills that put Congress’ approval ratings at slightly lower than “athlete’s foot.” Unable to wriggle out from underneath those votes, Feingold tried a little political jujitsu – vote for wildly unpopular legislation, tarnish the reputation of Congress, then try to score political points by running against the Congress that he aided in casting into disrepute.

The Republican Party of Wisconsin quickly fired back, highlighting Feingold’s vote for the health care bill, which is expected to cost $2.3 trillion over the next ten years, and Feingold’s vote for the $1 trillion “stimulus” bill. Somehow, they pointed out, Feingold let a few hundred trillion pennies elude his grasp.

Yet this pro-Feingold as served merely as an hors d’oevre to the television campaign the senator had up his sleeve. On July 13, Feingold began running an ad called “Just Say No,” in which he attacked RonJon for purportedly wanting to drill for oil in the Great Lakes.

The ad, which attempted to cash in on the still-fresh (and still-disastrous) BP oil spill, began like an erectile dysfunction commercial – with serene scenes of beaches and sunsets. Six seconds in, Feingold appears, talking about how he has “stood up” (pun unintended) to the big oil companies and opposed drilling for oil in the Great Lakes. As he accuses Ron Johnson of wanting to do that very thing, a graphic of a giant, amorphous oil slick moves from the Gulf of Mexico coast to Lake Michigan, hypothetically blanketing the hypothetical state in hypothetical sludge.

Days before Feingold began running his ad, Johnson had issued a statement saying he unequivocally opposed drilling in the Great Lakes. But Feingold’s assertion that Johnson supported drilling for oil in Lake Michigan was rooted in an interview Johnson conducted with the Wispolitics.com website in mid-June. Johnson was asked:

Wispolitics: Do you want to open up more of the United States – continental United States – to, to drilling? I mean, would you support drilling, like, in the Great Lakes for example if there was oil found there or (unintelligible) using more exploration on Alaska – ANWAR or those kinds of things?

Johnson: Yeah, you know, the bottom line is that, uh, we are an oil-based economy. And we’re really, there’s nothing we’re going to do to get off of that for many, many years. So I mean we just have to, we have to be realistic and recognize that fact, and you know, I, I, think we have to we have to get the oil where it is but we need to do it responsibly, we need to utilize, you know, American ingenuity and American technology to make sure that we DO do it environmentally, you know, sensitive and safely.

The crux of Feingold’s argument hinged on Johnson’s beginning his answer with the word “yeah.” When written, it could be construed that Johnson is agreeing with the entire line of questioning. But the audio clearly shows that RonJon only uttered “yeah,” in the sense of “yeah, I am acknowledging your question.”

This nervous tic of Johnson’s, answering any question posed to him with “yeah,” ended up being a big concern for his staff. They thought if Feingold was smart, he’d ask Johnson a question like, “so, you would get rid of social security for seniors, knowing that by making a change, that you believe needs to be done, it would help the next generation have social security in the future, because you support sustainable social security fund, right?”

In this case, simply beginning his answer with the word “yeah” ended up costing Johnson hundreds of thousands of dollars. RonJon had to write check after check to respond to Feingold’s ad based on his reflexive response. OnMessage Media, the national firm Johnson was using for his television ads, rushed furiously to get a counter-ad out the door explaining that Johnson never supported drilling in the Great Lakes.

The “drilling in Lake Michigan” attack isn’t one the Johnson campaign had anticipated, so their ad had to be cobbled together from scratch. Yet within 12 hours, the national ad guys had produced “Stuck in the Mud,” which not only criticized Feingold’s 28 years as a “career politician,” but also accused Feingold of being “the only Great Lakes senator to vote no” on a bill that banned drilling in the lakes.

The vote itself, dug up by one of the campaign’s Wisconsin researchers, was a good catch – only the way it showed up in the ad, it wasn’t true. Senators Hillary Clinton and Chuck Schumer of New York both voted against the law, and New York borders both Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Thus, Feingold wasn’t the only “Great Lakes senator” to vote no on the bill.

RonJon didn’t like the ad to begin with. And when this mistake was pointed out, it caused some friction between the Wisconsin and Washington D.C. arms of the campaign. (The campaign used various publications and entities that defined “Great Lakes States” differently. Some included New York and some did not.)

It was the D.C. guys that went ahead with the ad with the disputed fact, but the Wisconsin staffers thought that some of their east coast consultants were ignoring the media fallout.

“They’re not on the ground – their decisions have no impact on their lives,” one staffer complained. “We have to deal with the day-to-day onslaught of an aggressive state media that will blow up any issue it can.”

Three months to go. And soon, the campaign would have more to worry about.

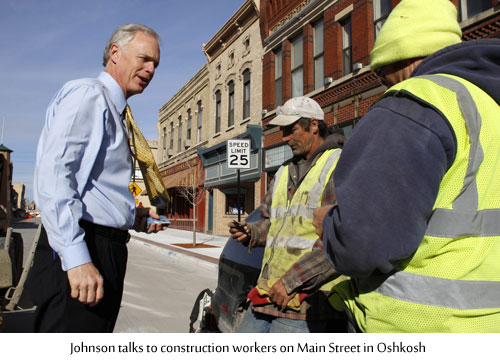

The third week in July, Johnson began a tour of the western half of Wisconsin. His public appearances in places like Hudson, River Falls, and La Crosse were limited primarily to “Tea Party,” or other like-minded events. The trip was planned stealthily, in order to avoid Johnson’s Democratic tracker coming along.

When speaking in front of these groups, RonJon often got too comfortable with his message. While it appeared he dodged a bullet by denying he wanted to drill in Lake Michigan, he soldiered on with his message that BP shouldn’t be vilified.

This caused much consternation with his staff, as they pleaded with him to stay away from anything but the most basic talking points on the whole BP issue. During one closed door meeting, they asked Johnson to tone down the BP rhetoric. “I will not stop defending the producers of America,” he shot back. At one point, he jokingly referred to some his staff as “professional liars” – as he was committed to running the campaign on his own terms. Johnson made it clear that if he was investing this much money and time, the campaign was going to stand for what he stood for.

To the Tea Party groups, Johnson’s free market rhetoric was like having liquid gold poured directly into their ears. Johnson believes strongly in the power of free markets and the ability of the private sector to pull Wisconsin out of the recession. And none of his campaign staffers would necessarily disagree with that philosophical foundation.

But they had a campaign to win. And as long as the man-made hole in the Gulf of Mexico belched out barrels of liquid disaster, it remained an open wound to Americans. Yet Johnson bucked his advisors, saying in one interview with a local newspaper, “I’m not anti-big oil.” (Translation: “I am pro-big oil.”)

As the campaign dodged bullets, Johnson began to think very fondly of his own campaigning prowess. As a result, he began tuning out his advisors even more, saying whatever came to his mind whenever he felt like it. “He thinks that he can win people over with arguments,” said one staffer. “That would be fine if this were a debate club – but this is a campaign,” the staffer added.

On this campaign swing, Johnson’s favorite trick was quoting verbatim entire glowing passages of what Milwaukee radio talk show host Charlie Sykes had said about him, despite nobody in Western Wisconsin knowing who Charlie Sykes was. Staff noticed peoples’ eyes glazing over when he began his typical Sykes spiel.

It didn’t help that Johnson was seeking counsel with political figures urging him to push his message forward in the way he saw fit. At one point, Johnson had a discussion with Newt Gingrich, who told him to ignore his advisors, because consultants were prone to mistakes by using the same political tools from the past. (Ironic, as Newt Gingrich has spent decades advising political candidates.)

The denouement of the late July road trip came when RonJon was in Prairie du Chien talking in front of about 20 people at the 3M plant. The plant’s employees asked him if he was a Viking or a Packer fan. (Johnson grew up in Minnesota, saying he only visited Wisconsin to drink beer with his friends, since the drinking age was lower.)

When Johnson replied that he was a Packer fan, the employees collectively began to boo him. After stumbling a little, he began to backtrack, saying that he still rooted for erstwhile Packer-turned Viking quarterback Brett Favre.

Amazingly, Johnson was willing to backtrack on the Minnesota Vikings, but not on BP.

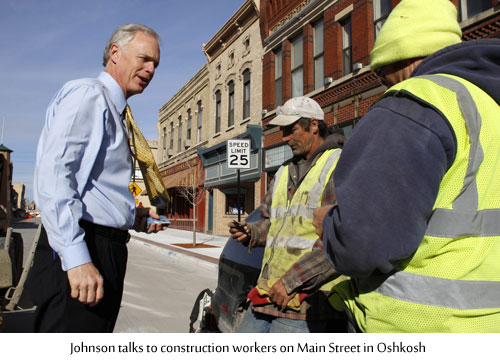

Back in Oshkosh, the campaign staff tried to assess the damage. During the trip, Johnson had repeatedly defended Big Oil. He called free trade “creative destruction,” implying that people had to lose their jobs to factories overseas in order to create new jobs here in America. He had said that “poor people don’t create jobs.” And Johnson expressed his opinion that people should be able to get their primary health care at Wal-Mart.

Again, on none of these issues was Johnson necessarily wrong. But the campaign trail isn’t necessarily the best place to introduce ideas to the public that require more than a fifteen second explanation. On all these things, the public needed to brought along gently.

Staff was most worried about the fact that the Democrats had pulled the tracker off Johnson. “I’m sure they have enough stuff by now. We’re creating new material by the day,” one staffer groused.

Part of that new material emerged soon thereafter, when RonJon said he would be selling his stock in BP in order to fund his campaign. The young chairman of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, Mike Tate, whose initial foray into politics has been slightly less successful than Travis Bickle’s, immediately pounced.

“Ron Johnson has been cheerleading for Big Oil on the campaign trail, saying that now isn’t the time to be beating up on oil companies,” said Tate in a statement. “In each and every case he didn’t say one word about the hundreds of thousands of dollars he had invested in BP and Big Oil. He’s not shooting straight with the voters.”

Some staffers were convinced that while Johnson had done reasonably well before controlled crowds, he wouldn’t go over so well in crowds of mixed ideologies. “He’s stubborn,” said one staffer. “He’s not going to shy away from cutting government, and that’s good. Really smart, but sometimes really stubborn.”

At this point, the behind-the-scenes “murder sessions” have gotten extremely tense. In fact, it is the campaign staff that is taking most of the barbs. When staffers suggested to Johnson that he shouldn’t defend the “Bush economic agenda” so stringently, he lashed out at them.

There were instances where they could tell Johnson was trying. On the morning of July 26th, Johnson was scheduled to do an interview with Wisconsin Public Radio’s Joy Cardin. In the pre-interview sessions, Johnson kept reflexively saying we need to drill for oil “where it’s safe, like the Gulf of Mexico.” Staffers kept reminding him that he couldn’t say that on the air, as the public didn’t necessarily consider the Gulf of Mexico to be a safe place to drill. Johnson nervously kept slipping it into his answers.

Sixteen minutes into the interview, “Larry from Neillsville” called in to ask Johnson if he’s ever told anyone it would be okay to drill for oil in the Great Lakes. Johnson said no, but went on to point out that America is an oil based economy. Then he said “we need to drill where it’s safe…” before pausing and moving on to another talking point. He stopped precisely where he needed to in order to avoid an ongoing story.

Even if his staff thought he was making progress, Johnson had already produced a Thanksgiving feast of cringe-inducing statements. And Feingold had his knife and fork ready.

On August 10, Feingold began running a radio ad he called “Stuff,” in which he plays an excerpt of RonJon indicating he was open to the “licensing” of guns “like we license cars and stuff.” The clip was taken months before Johnson had any campaign staff to explain to him that the word “license” to a gun owner is like the word “garlic” to a vampire.

What Johnson meant to say was that he supports allowing permits to carry concealed weapons, which is currently not allowed in Wisconsin. (It is one of the two remaining states that do not allow “concealed carry.”) But at the time, he didn’t know the political lingo, and misspoke.

Within a day, the Johnson campaign cut a radio ad explaining the mix-up. The script for the ad was actually written by RonJon himself, as many of the early radio ads were. It simply features Johnson’s voice, saying “in my first days as a candidate, I used the wrong terms when discussing my strong support for concealed carry rights for gun owners here in Wisconsin. I’m not a slick politician, and I made a mistake. It wasn’t the first time, and it probably won’t be the last.”

The Johnson campaign felt they had dodged a bullet, but worried that they couldn’t keep playing the “I’m just a confused new guy” card. “That’s going to be us from now on,” said one staffer.

However, Feingold’s gun rights attack on Johnson seemed a curious one, and exposes a small window into his view of himself. Nobody in Wisconsin seriously believed Feingold was somehow more of a defender of gun rights than the conservative Johnson. But Feingold actually thought the “maverick” tag he has hoisted upon himself would be enough to convince people. Soon, the ad faded away without any real effect.

Johnson’s staff felt they had turned a corner by the time mid-August rolled around. None of Feingold’s attacks appeared to be sticking to RonJon, and their candidate was learning to smooth out the message a little.

Ruesch’s life also got easier, as the campaign hired a new press secretary. Sara Sendek had come to work for Johnson after working on former congressman Pete Hoekstra’s unsuccessful campaign to become Michigan’s governor. Ruesch and Sendek hit it off immediately, moving in to an unfurnished, run down apartment together.

On Friday, August 13th (which would retroactively become ominous), the team began prepping Johnson for his Monday editorial board visit with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Wisconsin’s largest newspaper. The prep sessions were broken off into two-hour segments, and a wide spectrum of issues was discussed. Staffers lobbed questions at RonJon for a total of 10 hours in preparation for the interview.

On the morning of August 17th, Johnson and his staff made their way into the room with the Journal Sentinel editorial board. Once the interview began, Johnson dutifully soldiered through questions about Iraq, gun rights, health care, and tax cuts with characteristically laconic answers.

Then he was asked about global warming.

Johnson, who had previously characterized theories of man-made global warming as “crazy,” and “lunacy,” told the editorial board that he absolutely did not believe in the theory of man’s role in causing climate change.

“It’s far more likely that it’s just sunspot activity or just something in the geologic eons of time,” he said, adding that be believed excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere “gets sucked down by trees and helps the trees grow.”

Naturally, the headline in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel the next day read “Sunspots Are Behind Climate Change, Johnson Says.” After an hour of being posed dozens of questions, the paper had decided Johnson’s enthusiasm for sunspots was the show-stealer.

At no point in the 10 hours of interview prep were sunspots discussed. Staff was perplexed as to where it even came from – maybe Johnson had once read a book that briefly mentioned it and it just popped into his head.

After the article broke, the campaign was more worried about the second part of Johnson’s answer than they were about sunspots. “Excess carbon gets sucked down by the trees and helps them grow,” said one staffer. “He’s essentially saying pollution is good for the environment. Think that’ll sell?”

Of course, Feingold immediately attacked Johnson for his stance on man’s role in global warming. But in the same new article, Feingold made an equally puzzling assertion in an attempt to prove man-made global warming existed. “Do you notice the heat lately, my friend?” he told a Journal Sentinel reporter.

Obviously, if Ron Johnson had argued that global warming didn’t exist because he had to wear his fleece vest a few days extra last year, the paper would have destroyed him. But Feingold’s evidence – that it’s hot in Wisconsin in August – seems to be scientifically bullet-proof. Just stick your finger in the air to see if the world is on the verge of eradication. (If Feingold had been caught soliciting a prostitute, he’d be hailed by the newspapers as “creating jobs.”)

News of Johnson’s views on global warming went national. Jon Stewart joked on The Daily Show that Russ Feingold was going to lose “to some guy who thinks global warming is caused by sunspots and toaster ovens.” Basements all over the country were illuminated with lefty blog posts mocking Johnson.

Sendek, three days into her new job as press secretary, was cast right into the middle ofl’affaire sunspot. “Welcome to the campaign – our candidate just said pollution is good for trees. Have at it.”

Within days she was sending reporters emollient e-mails attempting to regulate the message. “It has been misconstrued to say that Ron believes sunspots are the sole cause for global warming” she wrote. “He has never made a statement that says sunspots are unequivocally to blame for global warming.”

Of course, amid the charges and accusations, one issue flew under the radar: do sunspots really have anything to do with global warming? The Journal Sentinel followed up with a respected researcher that said they do, but less so than greenhouse gases.

So it’s not as if Johnson was completely off base. For instance, he didn’t say global warming was caused by dolphin tears. But campaigns aren’t necessarily set up to introduce new, unknown facts into the public discourse. As P.J. O’Rourke has said, in the American political system, “you’re only allowed to have real ideas if it’s absolutely guaranteed you can’t win an election.”

While the Johnson campaign braced for calamity, the most unexpected thing happened:

Nothing.

Polls had shown the race to be a virtual dead heat since May. And even with all the hits Johnson had taken over the past two months, it appeared to still be a toss-up. A Rasmussen poll taken on August 24th, one week after the sunspot story broke, had Johnson up 47% to 46%. Only 5% of voters were undecided, with more than two months to go. Johnson’s missteps may have been pulling the campaign in one way, but the nation’s Tea Party zeitgeist was pulling the polls in the other direction.

In fact, the national media began to take notice. In late August, the New York Times ran a feature on the Feingold-Johnson race, calling it a “bellweather” for national G.O.P. hopes. It cast Johnson in a very positive light, even when Johnson was asked to comment on his frequent misstatements.

“I’m used to being in business, when you have a half-hour and you can hash things out, you can wax philosophical about things,” Johnson was quoted as saying. “It’s pretty hard to do in a political campaign when someone says, ‘What’s your position on this?’ And you get a microphone thrown in your mouth. That’s difficult.”

The conservative Weekly Standard was one of many right-leaning publications to begin featuring the “Ayn Rand-loving, pro-life Lutheran, plastics manufacturer from Oshkosh.” An article published on August 9th discussed RonJon’s public speaking style, saying “Johnson is personable and rolls off facts, figures, and anecdotes with ease when discussing the issues.”

Just as Feingold attempted to use his greatest weakness (being a career politician) to his own benefit, the Johnson campaign tried to pivot and make light of his occasional blunders.

On August 24th, Ron began running a television ad called “The Johnson Family,” in which his two daughters, wife, and son all extolled RonJon’s virtues. The grown children are intentionally made to look as if they are reading implausible compliments off of cue cards, before the music stops and Johnson admits to not being a career politician, nor are his kids professional actors.

The ad, written by Brad Todd at OnMessage Media, was an attempt at using humor to diffuse many of Johnson’s public statements. (The bar for a political ad to be considered “humorous” is pretty low – like being called the prettiest girl at a Rush concert.) But the ad itself, aided by the hundreds of thousands of dollars Johnson spent to air it, helped soften his public image.

On the other hand, Feingold had been making news with his television ads – but not in the way he intended. In early August, Feingold produced an ad called “Homegrown,” in which he tries to make the case that the stimulus plan he supported actually created jobs. The ad features a woman named “Elizabeth Ackland” attaching a new nameplate to her cubicle, to represent someone recently hired.

The Johnson campaign quickly scrambled to point out that there is no “Elizabeth Ackland” currently living in Wisconsin. It may seem like a minor point – campaigns use actors and fake names all the time – but it provided Johnson with a legitimate talking point: Russ Feingold couldn’t find a single living human being that benefited from the stimulus, so he had to make one up.

In mid-August, Feingold began running an ad called “On Our Side,” in which he proclaims his allegiance to “regular folks” over special interests. Yet one of the “regular folks” featured in the ad was a lobbyist for the AFL-CIO. According to Project Vote Smart, Feingold had a 94% rating from the AFL-CIO until 2009, which doesn’t exactly buttress his “maverick” persona.

But that didn’t keep Feingold from going on offense, even if Johnson was sharpening his message.

On the morning of August 30th, Johnson was set to conduct an interview with the Wisconsin Radio Network. When the radio interview started, Johnson began talking about entrepreneur Steve Wynn moving jobs to China. “He’s also creating resorts in Macau in China, communist China. And his point is, the level of uncertainty, the climate for business investment is far more certain in communist China then it is in the U.S. here,” he told the host. “We’ve created such a high level of uncertainty in this economy because, quite honestly because of the agenda that Senator Feingold represents.”

After the interview, Ruesch counseled against mentioning Wynn, thinking it would only invite more questions. Dissatisfied, Johnson asked for Jablonski’s second opinion. Jack told Johnson he tentatively agreed with Ruesch.

Of course, saying jobs are moving to China is normally an innocuous observation. But the Wisconsin State Journal published an article about Johnson’s statements, wondering if “RoJo” was a “big fan of China.” Obviously, had Feingold accurately noted that jobs were moving to Hong Kong, he’d be hailed as standing up for working people. When Johnson did it, it was as if he had pledged allegiance to Chairman Mao.

Wisconsin State Journal reporters tweeted a link to the story, saying the story “Could go national.” Surely, they were hoping it did. This suddenly emerged as a theme for Johnson – not only do politicians and staffers use campaigns as a ladder to move up, but members of the media do, too. If a reporter could manufacture a “gotcha” moment with a gaffe-prone candidate like Johnson, their name could be all over the national blogs.

The day after the story “broke,” Feingold was a guest on “The Ed Show” on MSNBC. He told host Ed Schultz that Johnson was “coming unraveled” before he responded to Johnson’s comments on China. “Here’s a guy who claims to be for freedom, who claims to be for free enterprise and jobs, who’s praising the communist Chinese system over our system,” Feingold said. “That’s not going to play well with the people of Wisconsin.”

After watching the interview, Jablonski laughed. “Well, I guess ‘Rojo’ is Spanish for ‘red,’” he chuckled.

Once again, however, Feingold’s swipe failed to connect. While the last Rasmussen poll, taken August 24, had the race a virtual tie, internal state GOP polling had Johnson pulling slightly ahead. According to the poll, Johnson was overperforming in traditionally Democratic areas, and slightly underperforming in strong Republican districts. For instance, Johnson was only up 51% to 46% in the Milwaukee suburbs, where he was almost certain to win by twice that margin.

“Jesus Christ,” said the characteristically pessimistic Jablonski. “We might actually win this thing.”

PART III: SOMETIMES YOU JUST SAY STUFF

The day after Labor Day, September 7th, is colder than usual this year in Wisconsin. The farm houses around Oshkosh are already framed with trees dappled orange and red, and one can already see his or her breath. (Using Russ Feingold’s logic, this is proof that global warming doesn’t exist.)

The parking lot at the Johnson headquarters on Oregon Street is now full of cars, as the campaign’s statewide staff has grown to 51 employees. Visitors are greeted by a dog named Bourbon, a Shar Pei owned by Kirsten Hopkins, Johnson’s principal fundraiser.

Numerous staffers now occupy the rows of cubicles in the headquarters. They all walk with pieces of paper in their hands, as if the fate of the campaign hinged on whatever information they are carrying. Johnson’s kids, Ben and Jenna, also working on the campaign, wander the halls. They are easily recognizable, given their ubiquitous position on televisions all over the state. Given, they’re not exactly “stars” per se, but this is Oshkosh, Wisconsin – they might as well be Tom Cruise and Miley Cyrus.

Johnson is sitting at a large wooden desk in his office, getting ready to do a national interview with Sirius XM Satellite Radio. Sendek sits across from him with a pad in her hand. As he discusses pension issues with the host, he scribbles a drawing representing a sun, with lines shooting out of it.

The interview seems to be the standard Ron Johnson interview – he throws out statistics, while seeming a little short of breath. His hands shake a little. But then, Johnson’s asked a question about health care, and the whole interview dynamic shifts.

He begins discussing his daughter Carey, who was born with a heart deformation 27 years ago. At the time, her specific disease was considered to be 75 percent fatal. Johnson went from doctor to doctor, searching for one that could perform the procedure to save his little girl’s life.

And it is golden. Suddenly, by talking about something from his own experience, Johnson has come to life. Like flipping a switch, he has gone from being a candidate to a dad.

After the interview, we talk about some of his verbal flubs. I ask him about sunspots. He shrugs. “Sometimes you just say things,” he says. I ask him if he thinks reporters are purposely trying to trip him up now. “Absolutely,” he answers.

He says his staff has been working with him on committing errors of o-mission rather than errors of co-mmission. Nobody will ever criticize you for something you don’t say, they have told him. But he is now aware that things he does say can cost him a million dollars’ worth of ads.

The conflict in Johnson is evident – he got into the race because of his disgust with smooth-talking politicians. But now, he’s struggling to become a plausible politician himself. People say they want an outsider, but once a candidate gets too outside, it harms their brand. (Ask Republican Delaware Senate candidate Christine O’Donnell, whose past statements forced her to cut a television ad publicly denying she is a witch.)

Most of September would be spent raising money, issuing new television ads, prepping Johnson for the debates in October, and fending off Feingold’s attacks. But one minor inconvenience stood in the way: RonJon had to win the primary on September 14th.

To most political observers, Johnson’s primary victory over Dave Westlake was a mere formality. Westlake had run a campaign with virtually no money – he sold blaze orange t-shirts to raise cash, and posted internet videos of himself giving impassioned speeches about liberty. In these videos, Westlake very much resembled Wisconsin native Chris Farley’s famous “Matt Foley, Motivational Speaker” character. And it wouldn’t surprise any voter if Westlake himself were living in a van down by the river.

During the campaign, Westlake had criticized Johnson for not being sufficiently right-wing, hammering him particularly on RonJon’s support for the Patriot Act. But Westlake’s credibility was damaged irreparably when the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel unearthed some of the details of Westlake’s business dealings. (The Johnson campaign denies they had anything to do with leaking the details.)

Westlake was being sued by a former business partner, Fawaad Khan, over a business they owned together called High IQ, LLC. Private e-mails between Westlake and Khan released to the public not only showed Westlake to be whiny and evasive, but exposed his disastrous business plan. Basically, Westlake had taken out government loans to pay himself a salary while he traveled the state campaigning for U.S. Senate, instead of using those funds to benefit the business. Thus, the “real conservative” candidate was depending on government aid to run his campaign.

It’s not reassuring to voters when it becomes clear someone is running for office simply because they are virtually unemployable anywhere else. So on election night, Johnson beat Westlake by a USA versus Angola Olympic basketball Dream Team margin – 85% to 10%. Given the nature of polls – for instance, 10% of Americans think Dick Cheney secretly planned the 9-11 attacks – the Johnson campaign considered this to be a virtual sweep of Republican voters.

While the primary was a mere formality, the news following September 14th proved to be a bit of a surprise. A Rasmussen poll conducted the day after the primary showed Ron Johnson up 51% to 44% on Feingold. The campaign had expected a post-primary bump, but not that kind of bump.

Seeing his numbers begin to slip, Feingold began to step up his attacks on Johnson. The first came in the form of a television ad Feingold ran featuring news footage from a Madison television station that investigated whether Johnson had gotten government assistance to start his business 31 years ago. It includes a clip of Johnson saying he never lobbied for “special treatment or a government payment,” then shows headlines indicating Johnson received $4 million in “government” loans to aid his business.

At issue were a tool called “Industrial Revenue Bonds, (IRBs),” which grant a business a lower interest rate for loans which the business has to secure from the private underwriting market. There is no government guarantee, no government money, and the taxpayers are never at risk – and Johnson’s company paid it all back on time.

In order to counter this attack, Johnson’s campaign contacted two former Wisconsin secretaries of commerce, Bill McCoshen (who served under Governor Tommy Thompson) and Dick Leinenkugel (whose service under Democratic Governor Jim Doyle killed his own chances of running for the GOP senate nomination Johnson eventually won.) The two secretaries wrote a letter pointing out that IRBs aren’t “government aid,” as Feingold’s ad suggested. In fact, the program urges government to get out of the way to provide more business growth – a position on which Johnson had been wholly consistent.

This was a Feingold charge for which the campaign had been prepared. In fact, it was one of many potential Feingold attacks that Johnson had anticipated. While it’s much publicized when a candidate hires a private investigator to dig up dirt on his or her opponent, more often a candidate will hire someone to investigate his or herself. This gives a candidate an idea of what negative information their opponent is likely to use against them. Johnson’s campaign did just this, so they already had a good list of the attacks Feingold was likely to launch.

In fact, the tricky part of running a campaign isn’t knowing what will be used against you, it is guessing when those things will be employed by your opponent. Way back in July, Jablonski assumed Feingold’s next negative attack on Johnson would be on free trade issues. That attack came, but not until mid-September, when Feingold began running ads accusing Johnson of supporting international trade agreements like NAFTA, which Feingold said cost Wisconsin 64,000 jobs.

In late September, word got to the Johnson campaign that Johnson would be attacked for his involvement in the Catholic school system in the Green Bay and Fox Valley areas. For years, Johnson had donated millions of dollars to various Catholic schools in Northeastern Wisconsin, despite not even being Catholic himself.

When a bill came before the Legislature to lift the statute of limitations for people who want to accuse the church of sex crimes, Johnson opposed it. He thought that it could make the very system he helped keep alive a magnet for lawsuits that could bankrupt it. While he supported tough criminal penalties for pedophiles, he didn’t want to see all the good he was trying to do torn apart by 30-year old lawsuits. He also worried that such “window” legislation could harm other non-profits like the Boys and Girls Clubs.

On September 28th, a publication called “Veterans Today” published the video of Johnson’s testimony against the bill before the Wisconsin Legislature. In the video, a bearded Ron Johnson, looking like a skinny Wolf Blitzer, reads through his objections to the bill. A bill, incidentally, on which the Democratic-controlled Legislature agreed with Johnson. It never passed either house.

Nevertheless, the Johnson campaign took proactive measures to get ahead of the story. The left-wing blogosphere (where spelling and proper English are treated as if they were prisoners in Guantanamo Bay) pounced immediately, posting “Ron Johnson supports pedophiles” entries everywhere. On Keith Olbermann’s MSNBC show (which The Weekly Standard’s Matt Labash described as “the sound of a man having unprotected sex with the sound of his own voice”), Olbermann had an adult victim of pedophilia on the air to discuss his disgust with Johnson.

But Johnson’s campaign was ready. They issued a fact sheet on the allegations that Ruesch had actually drafted back in June while working at the state Republican Party. Johnson called for full disclosure by the Green Bay diocese in any ongoing investigations. Calls were made to media outlets all over the state to explain why this was a non-story.

And it worked. A story on the subject by Milwaukee Journal Sentinel investigative reporter Dan Bice rumored to be following the allegations never materialized. (Bice had done an article on the issue two months earlier.) The story faded, at least for the time being.

But it didn’t mean the campaign was out of the proverbial woods just yet – there was still material out there that could be used against Johnson. Running a campaign is very much like the movie Carlito’s Way – just when you think you’ve escaped, Bennie Blanco from the Bronx returns from the past to take you out.

And the left-wing blogs kept trying. Their next charge was that Johnson had once hired a sex offender in his plastics plant. Never mind that in any other circumstance, these same liberals would be all for giving ex-cons a second chance at employment. But in Wisconsin, it is actually against the law to take someone’s arrest or conviction record into account when deciding to hire them. If Johnson hadn’t hired this guy, he would have been breaking the law – and the blogs would use that against him. But because he did hire this man, feeling he had been rehabilitated, that was then used against him.

Again, none of the attacks stuck. A Rasmussen poll taken on September 29th had Johnson up by an unbelievable 54% to 42% margin. The day before, RonJon had issued two new ads – one featuring Johnson standing in front of a white dry-erase board writing down the number of lawyers that currently serve in the Senate (57) as opposed to the number of accountants (1) and manufacturers (0). In the initial shoot for the ad, the numbers were wrong, so the ad had to be re-shot and some CGI blurring added to correct the numbers on the board.

The second ad was slightly more negative in tone. (Campaign rule: if your opponent is running a negative ad, it’s called a “negative ad.” If your campaign running a negative ad, it’s called a “contrast ad.”) The ad criticized Feingold’s vote for the health care bill, noting that before the bill passed, 55% of Wisconsinites opposed a “government takeover of health care.” (The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel eventually labeled the entire ad as “false,” as they incredibly didn’t believe the bill amounted to “government healthcare.”)

It wasn’t a hard-core negative ad, though – the health care bill is fair game under any circumstance. Jablonski said that, given Johnson’s big lead, the plan was to stay positive. “Even if they start running ads with video of a fake bearded Ron Johnson sex offending,” he said.

In that vein, the campaign cut an ad with Johnson and his daughter, Carey, discussing her heart problem at birth. But it needed to be re-shot, because they felt Johnson didn’t deliver his lines with enough emotion. The goal was to get a positive ad on the air featuring Carey, who “presents well on TV.” (Campaign-speak translation: “she’s attractive.”) Eventually, they shelved the ad altogether.

Yet Johnson’s ads – simple, yet effective – were the envy of campaigns around the country. Brad Todd, of OnMessage Media, said when producing an ad, his competition isn’t the other candidate – it is the ad that airs directly before and directly after his campaign ad. “What you produce has to hold a viewer’s attention and look like it belongs will all the other ads on the air,” he said.

Soon, Johnson’s measured, disciplined campaign was starting to get national recognition. At the Washington Post’s “The Fix” blog, Chris Cillizza said Johnson “has run one of the best — if not the best — Senate campaigns this cycle.” The Oshkosh Northwestern, Johnson’s hometown paper, called his campaign staff “brilliant.” The Washington times said RonJon, “aided by a smart and savvy campaign staff, has refined his message and appearance.”

But Feingold wasn’t helping his own case, either, stumbling into a few uncharacteristic missteps. For instance, one of the senator’s favorite talking points during the campaign was that he has been outspent in every one of his Senate races. For this oft-repeated claim, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s “Politifact” feature gave Feingold a “Pants on Fire,” rating as he significantly outspent challenger Tim Michels in 2004.

For weeks, Feingold had said he would not be attending a campaign rally held partly for his benefit by President Obama on September 29th. At the very last minute, Feingold appeared at the rally, leading to suspicion that he had been hectored by the White House to attend.

In an interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel editorial board, Feingold complained about Johnson’s insistence that the 18-year senator was a “career politician.” “I think it’s a pretty sad thing for our society when somebody runs a campaign telling young people, ‘Don’t you dare go into public service, or you’re going to be mocked,’” Feingold told the board. Of course, it was Feingold that, within weeks of joining the race, called Ron Johnson a racist and a communist sympathizer, and had fabricated his positions on numerous issues. So exactly who was keeping people from entering politics? Did Feingold expect a telethon for three-term U.S. senators?

Feingold even bumbled some of his television ads. On October 1st, he began running an ad bragging about his vote for the poisonous health care bill – a bill that, according to Rasmussen, 57% of Americans wanted repealed (46% “strongly.”) At the end of the ad, two women urge Ron Johnson to “keep your hands off my health care.” As if people couldn’t figure out that a government takeover of health care is the ultimate “hands on” approach to medical care. From watching the ad, one would get the impression that it was Ron Johnson who wanted to take over health care – in fact, it was obviously the exact opposite.

But that paled in comparison to Feingold’s next TV ad blunder. On October 5th, the Feingold campaign ran an ad accusing the Johnson campaign on “dancing in the endzone” too early. The video featured a clip of one of the most notorious moments in recent Wisconsin sports history – then-Minnesota Viking Randy Moss mooning the crowd in a playoff victory over the Green Bay Packers at Lambeau Field. (In an odd twist, Moss was traded back to the Vikings from the New England Patriots the very day the ad began running.)

As soon as the ad began running, the Johnson campaign sprung into action, personally calling the National Football League offices. Since anyone who has ever watched an NFL game knows that footage of the games is copyrighted material, the Johnson campaign suspected Feingold hadn’t gotten clearance to use the clip in his ad. As they soon found out, the clip was used without permission.

That very afternoon, Feingold had to pull the ad off the air via NFL directive. Perhaps most ironic, however, was the fact that here was Russ Feingold – who had made a career of telling people what was permissible to put in television ads – having to cancel his own ad for using illegal material.

Feingold’s missteps helped Johnson stay ahead in early October: a poll released by an organization called “We the People” showed RonJon up 49% to 41% on October 4th. But that didn’t necessarily mean all was well with the campaign staff.

In fact, the pressure to win was now causing some significant fissures within the staff. This is common with campaigns – by the end, people who have been trapped in a headquarters for months can barely stand the sight of one another. But amongst the Johnson campaign staff, these divisions ran deep.

Many of the staff had to move desks in the Johnson headquarters to avoid seeing staffers from other departments. Some staffers appeared to be more worried about positioning themselves for a job with Senator Johnson than doing the work they had been assigned. There was talk of firing a number of the more troublesome campaign workers, but it was decided that, with a month to go, there’s no way the campaign could train replacements.

The campaign was also fending off political consultants trying to work their way into the operation. Three months earlier, when Johnson was a longshot, the campaign had struggled to find help. Now, with the polls showing RonJon well ahead, consultants began to descend like locusts, offering their advice on how to run the campaign. Undoubtedly, these consultants would then pad their resumes, taking credit for having “worked” on the expected stunning Johnson win. If victory has a thousand fathers, the Johnson campaign was quickly becoming the Maury Povich Show of campaigns.

The campaign was also fending off pressure from national politicians to allow them to come to Wisconsin to campaign on Johnson’s behalf. Seeing as how Johnson was running as the anti-politician, a decision was made to turn almost all of them down. “You name the national Republican figure, and we told them there were better places they could be,” said one staffer.

Some state representatives and senators were calling regularly to offer their directives. One state senator called to tell the campaign they could improve Johnson’s numbers by buying an ad in a political leaflet printed in a Milwaukee-area conservative activist’s basement. Other state legislators, many of whom had never run a competitive race, called on a daily basis to offer their advice.

Perhaps the most unexpected time-consuming task was given to the campaign by school teachers. All over the state, teachers were assigning their students the task of asking a senate candidate a question. As these requests came flooding in, staffers had to handle each of them individually. (They were never signed as if they were coming from Johnson; they were always attributed to the staff member handling it.)

But even with all of these sudden pressures from the outside world, the campaign had to internally deal with their most daunting task of all:

Johnson had to get ready to debate of the U.S. Senate’s most capable orators, Russ Feingold.

PART IV: A SHOT AT THE KING

Ron Johnson’s debate preparation had actually begun in earnest more than a month before the first scheduled matchup with Feingold on October 8th. Feingold, likely thinking he could handle the newcomer Johnson fairly easily, had proposed six debates, Johnson agreed to three.

Mark Graul, who had run Congressman Mark Green’s unsuccessful race for Wisconsin Governor in 2006, was brought in to help with the debate preparations. (Ruesch said she was pretty sure they were paying Graul with Arby’s coupons.)

Initially, a larger team was in the room during debate prep, but the more people in the room, the more Johnson bristled. So attendance in debate prep was scaled back to only the essential staffers.

Early on, there were rumors that the campaign would get national conservative darling Congressman Paul Ryan to play the part of Feingold during debate sessions. In his youth, Ryan’s father actually worked as an attorney in the same Janesville building as Feingold’s father. This would have been quite a scene – seeing a nationally recognized free market stalwart like Paul Ryan strenuously arguing for higher taxes and greater government involvement in health care.

But Ryan’s schedule couldn’t accommodate the commitment. Instead, the campaign enlisted the help of attorney Chris Mohrman, a former member of Governor Tommy Thompson’s administration. To play the part of Russ Feingold, Mohrman returned from Washington D.C., where he was working for a national virtual schools organization at the time.

From the beginning, the campaign knew their strategy for the debates: just don’t make any news. Senate debates are universally watched by no one – you can’t win a campaign by performing well, but you can certainly damage your campaign by saying something that can be used in a television ad against you.

In other words, in a debate against Russ Feingold, a tie is a win.

Johnson and his staff spent the better half of September locked in a room, practicing his debate tactics. It didn’t always go well. At times, Johnson was irritated and irascible, objecting to the questions he was asked. Sometimes, he would throw his papers up the air and walk out of the room. His staffers initially sensed that he was mad at himself for not knowing more of the material, but they eventually figured out he was just as mad at them for not preparing him well enough.

Johnson encouraged a more inclusive method of debate prep, where he could sit around a table with his staffers and discuss issues before distilling what he learned into usable sound bites. He complained that his staff continued to “murderboard” him. (Johnson uses the term “murderboard” like a terrorist would use the term “waterboard,” and it isn’t coincidental.)

During one particularly grueling session, Johnson and staffers debated a detail regarding Social Security. It was important that Johnson get the Social Security issue down pat, as it is one of the bedrock issues Democrats use to demagogue Republicans.

In the days before the debate, Feingold had telegraphed where he would attack Johnson during the debate. He’d go after Johnson’s lack of specifics on economic issues, and his lack of a plan to turn the economy around. The campaign staff worked hard to give Johnson a rejoinder to this line of criticism.

Feingold clearly would also deem himself the “underdog” in the race, so campaign staff prepared Johnson to say Russ was the underdog only because he had made himself so through his bad votes. “If the A&W Root Beer Bear was in the race, he’d call himself the underdog, too,” cracked Jablonski. Sadly, the campaign opted not to put this line in Johnson’s preparation materials.

Johnson himself had watched tapes of Feingold’s previous debates in order to prepare. The campaign saw how aggressive the senator was in criticizing challenger Tim Michels during the debates in 2004. If Feingold was that truculent when he was up in the polls by double digits – how much would he attack being substantially behind?

Adding pressure to Johnson’s first debate was the reputation he was earning as a “no show” candidate. Word was spreading that Johnson’s campaign was keeping him away from public appearances to avoid the gaffes that plagued his campaign during its early days. Don Walker of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel wrote an article complaining that Johnson wouldn’t release his daily calendar to the media. (Feingold wouldn’t release his calendar, either, but that fact didn’t seem to fit the media narrative that Johnson was avoiding public appearances.)

Thus, given his limited appearances in September, people were anxious to see how the new candidate would match up against one of the Senate’s most skilled debaters. But debate preparations were still going poorly. As of three days before the Friday night event, one staffer said that debate prep was “off the rails.”

As Friday approached, it was still unclear to staff how the debate would go. It was possible, given Johnson’s willingness to make fun of his own gaffes, the public would be more willing to forgive any misstatements he made. In 2008, the public’s expectations of Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin were so low, many people actually believe she debated rival Joe Biden to a draw. Whether RonJon managed expectations to a similar degree was yet to be seen.

In the final debate prep before the big show, staff said they thought Johnson wasn’t nervous at all. One staffer said Johnson looked “terrified” before he left Oshkosh, but another said he was more “stressed” than afraid. The grueling debate prep had sapped him of his energy. He was accompanied to the Milwaukee debate by Ruesch, Sendek and Juston. Johnson took a nap in the RV on the hour and a half drive south.

When they arrived at the television studio on the Milwaukee Area Technical College campus, Ruesch took her place in the holding room, where she began to prepare press releases. The other staff were in the studio, with Sendek tweeting the proceedings.

The debate began with moderator John Laabs explaining the Wisconsin Broadcasters Association (WBA) preference that candidates not use video of the debate in political ads against their opponent. Johnson agreed to the policy; predictably, Feingold did not. (Just that day, an independent group began running ads against GOP gubernatorial candidate Scott Walker, using footage from his earlier WBA debate.)

And then it began. Even if a candidate has millions of dollars to spend, the best staff in the world, and a lead in the polls, debates are a different world. It’s just two candidates, two microphones, and dozens of people watching at home. There’s nowhere to hide.

Feingold was first to give his opening statement. He began by mentioning that he was born and raised in Wisconsin – a subtle shot at Johnson’s Minnesota upbringing. Feingold stressed his independence on trade agreements and the Wall Street bailout. As expected, he criticized Johnson’s lack of specifics on issues.

Then, it the time everyone was waiting for. Johnson began his opening statement, explaining that he had no political aspirations, and that running for Senate was not his life’s ambition. In an unexpected twist, he actually took some direct shots at Feingold, criticizing his vote for the health care bill and for expanding the nation’s debt. Johnson finished by emphasizing his status as a potential “citizen-legislator.”

As the questions began, Johnson looked nervous, but was hitting his talking points. On a question about health care, he stumbled a little before inevitably getting to his birth story about his daughter. In his answer to a question about energy, he used the phrase “exploit our oil resources,” which he had worked to avoid in debate prep. But it was a minor point.

When both candidates were asked about global warming, Johnson inexplicably defended his position with regard to sunspots. Staff pleaded with him to drop that talking point, but he soldiered on. “He just can’t help himself,” said one staffer.

About halfway through, one thing became evident: Ron Johnson was actually hanging in there with Feingold. In fact, he was landing a few punches of his own. This risk seemed to pay off, as Feingold wasn’t able to refute many of Johnson’s criticisms. As Omar says inThe Wire, “if you take a shot at the king, you best not miss.”

Feingold wasn’t necessarily helping his own cause. He jabbed repeatedly at Johnson, but did so with an oleaginous grin, as if he were a traveling salesman pitching mustache wax from the back of a truck. At one point, he criticized Johnson for agreeing with President Obama on some issue, but disagreeing with Obama on others. In the very next line, Feingold bragged that he agreed with President Bush on immigration reform.

At one point, Johnson predicted Feingold would accuse him of wanting to “privatize” Social Security, and pre-butted the accusation. Predictably, Feingold went right on to accuse him of wanting to privatize Social Security.

Even more oddly, Feingold resurrected his trial balloon from June, in which he appealed to Tea Party members for their votes. Again, he tried to make the case that he is truly the Tea Party candidate, given his vote against the Patriot Act – which demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the Tea Party movement. Yet it was telling that while once Feingold publicly derided Tea Partiers, he was now attempting to court them.

Afghanistan was one of the issues Johnson’s staff thought would give him the most trouble, but he navigated it smoothly. Same with stem cells, which could have been problematic had Johnson not handled it as well as he did.

Throughout the debate, Johnson got more comfortable. But he looked nervous. To television viewers at home, it appeared as if a bead of sweat had run down his forehead and across the bridge of his nose. Had he not already been gaunt, he probably would have lost five pounds in perspiration.

When the one hour debate ended, it was clear: Johnson didn’t exactly win on style points, but more than held his own on substance. It was like a naked steak on a plate – lacking in presentation, but to the Johnson campaign, ultimately satisfying.

While Johnson could decompress a little after the Friday night debate, that relaxation was short-lived. There were only two days until the second debate, to be held in Wausau on Monday.

While it would make for a grueling four-day stretch, it worked to Johnson’s advantage to get two of the debates out of the way in such a short period. Plus, the second debate would fortuitously be held on the same night that Brett Favre was returning to play his former New York Jets team, after he was accused of sending cell phone pictures of his penis to a former female Jets employee. Given Wisconsin’s fascination with the former Packer legend, the number of viewers for the second debate would make the first debate look like “Dancing with the Stars.”

Johnson’s campaign immediately began reviewing film of the Milwaukee debate, breaking it down Vince Lombardi-style. In retrospect, they understood how eerily dead-on Mohrman’s portrayal of Feingold in debate prep had been. Not only had he nailed Feingold’s rhythm and inflection, he actually predicted the actual companies Feingold would cite when bragging about stimulus jobs created.

Johnson’s team scrambled to come up with rejoinders to some of Feingold’s lines in the debate. They needed something for Johnson to say when Feingold pulled an obscure issue from out of nowhere. For instance, in the first debate, Feingold mentioned a New Zealand trade compact that he said would hurt the dairy industry in Wisconsin. Johnson had never heard of the compact, and his response was a little disjointed.

In between the debates, a story ran on Politico.com that gave readers a glimpse of Johnson’s displeasure with overly “handled” on the campaign trail. “So he watches his words, ignoring the fact that he’s already making the trade-offs conventional politicians make to win office,” wrote Jim VandeHei, a Wisconsin native. “It will be different once and if he wins, he promises. Then, his true feelings can take voice.” (Translation: you think the shit I say is crazy now, wait until I’m elected!”)

The second debate itself wasn’t as pressure-packed as the Milwaukee debate, as it wasn’t televised anywhere outside the Wausau area. The format was more conducive to discussion between the candidates, and that showed up in a volatile discussion about campaign finance reform nearly halfway through the debate.

Several days earlier, Feingold’s campaign had accepted over $600,000 from the liberal group Moveon.org. This was the same group that in 2007 had run a full page ad in the New York Times calling the American Commanding General in Iraq, David Petraeus, “General Betray-Us.” (Since Petraus was picked by President Obama to lead the American forces in Afghanistan, this reference has conveniently been scrubbed from the MoveOn.org website.)

Earlier in the debate, Johnson asked Feingold why he didn’t vote to condemn the “General Betray-Us” ad, as a majority of the Senate had. Feingold remarked that this group had the right to “free speech.” Later, however, Feingold called on Johnson to tell “extreme” third party groups to stop running independent ads on Johnson’s behalf. Johnson responded that these groups, too, had the right to free speech.

What Johnson missed was the chance to ask Feingold – “if these third party groups are so ‘extreme,’ why did you just accept $600,000 from one of them?” Staffers were kicking themselves after Johnson missed this softball – but then again, this debate was nearly invisible. Any shot landed against Feingold would be just as quiet as a shot landed against Johnson. And in the end, that benefited RonJon a great deal more. (More importantly to Wisconsinites, Brett Favre threw a late-game interception to lose the game for the Vikings.)